JOIN OUR WHATSAPP GROUP. CLICK HERE

Negative impact of Drought in South Africa

Negative impact of Drought in South Africa Welcome to Describe Negative impact of Drought in South Africa Easy Question From this Article you will Get to know the Meaning and Definition of Drought Especially in South Africa and Other African Countries At all,The Causes and Factors of Drought South Africa case study, and The Impact of Drought in south Africa.

What is drought?

Drought is caused by a lack of rainfall, causing serious water shortages. It can be fatal.

Unlike other extreme weather events that are more sudden, like earthquakes or hurricanes, droughts happen gradually. But they can be just as deadly as other weather hazards—if not more so: Drought has affected more people in the last 40 years than any other natural disaster.

The severity of drought worsens over time. When it arrives, drought can last for weeks, months, or years—sometimes, the effects last decades.

What causes drought?

Droughts can be triggered by natural causes such as weather patterns. But increasingly they are caused by human activity.

Manmade causes include:

- Climate change – global warming makes extreme weather more likely. It can make places drier by increasing evaporation. When land becomes so dry, an impermeable crust forms, so when it does rain, water runs off the surface, meaning sometimes flash flooding occurs.

- Deforestation – plants and trees release water into the atmosphere, which creates clouds and then rain. Bad agricultural practices like intense farming not only contribute to deforestation in the first instance but also affect the absorbency of the soil, meaning it dries out much quicker.

- High water demand There are several reasons water demand might outweigh the supply, including intensive agriculture and population spikes. Also, high demand upstream in rivers (for dams or irrigation) can cause drought in lower, downstream areas.

The Impact of Drought on Africa

Water scarcity is a serious concern everywhere,

Water scarcity is a serious concern everywhere, but it is particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Africa as a whole. According to a recent Southern African Development Community (SADC) research, the Kingdom of Lesotho, the Republic of Malawi, the Kingdom of Swaziland, and the Republic of Zimbabwe will all need to declare national drought disasters by the middle of 2017. The Republic of Mozambique and the Republic of South Africa, two nations in Southern Africa, have both proclaimed partial drought emergencies. While December 2015 was one of the hottest months in recent memory, the three months from October to December 2015 were the driest on record in the previous 35 years. Due to a lack of adequate water, cholera epidemics and food shortages were widespread in the area.

According to the SADC Situation Update for 2015/2016, the 2015/2016 rainy season was expected to have high temperatures and insufficient rainfall based on meteorological forecasts. Governments in the South African region took action to lessen the effects of the drought. Programs like increased food storage, water restrictions, and water conservation programs were put into place. The effects of the drought, however, demonstrated how dire the situation was[1].

The old and inadequate water distribution and retention infrastructure in the area was one of the main causes of the failure to effectively combat the drought. Despite the continent’s tremendous population growth at the turn of the century, no new construction was added to the water retention infrastructure, such as dams, that was completed in the 1960s or 1970s. This might be caused by the fact that most national governments don’t have enough funding. However, significant construction is planned for South Africa, notably the Umzimvubu Dam in the Eastern Cape and the new Inkomazi Dam in KwaZulu-Natal*1.

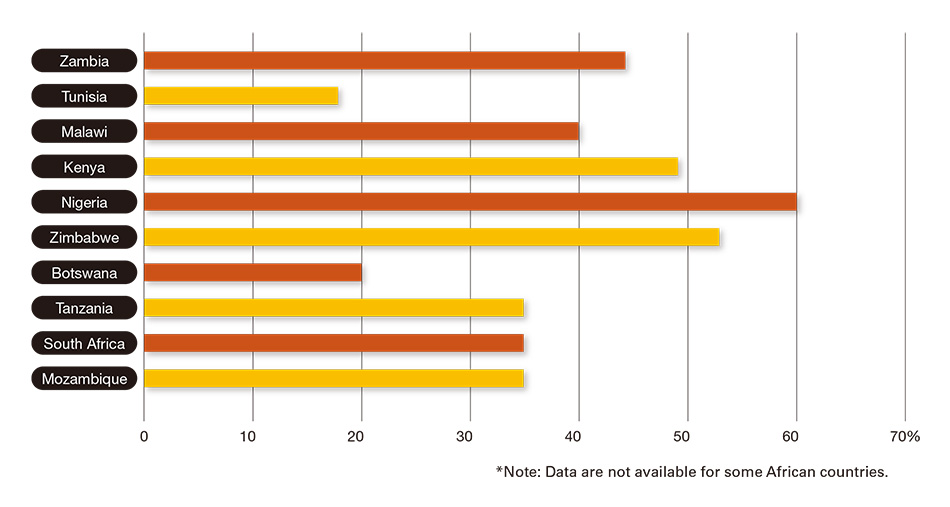

Massive water loss that could have been prevented was also a result of aging infrastructure, such as outdated pipe networks. Non-revenue water loss, or the difference between the amount of water input into the water distribution system and the amount of water paid to end consumers, is over 35% in South Africa, 40% in Malawi, 20% in the Republic of Botswana, and over 53% in Zimbabwe. Other African regions have seen comparable patterns (see Figure 1)[2].

*1 The verdict in this case is still pending.

2. Drought Interventions and Preparedness

Drought Interventions and Preparedness Several interventions were implemented by various governments across Africa, from the national level to the local or municipal level.

In South Africa, the government’s approach was to start a campaign to educate the populace to use water wisely. This educational campaign was rolled out across the tiers of government and water agencies in the country. In addition, efforts to reduce water leakages and losses were increased at the three tiers of government through an approach to maintain existing infrastructure and facilitate the conservation of water in the system[4].

In countries like the Republic of Namibia, a program has been rolled out called integrated water resources management, which focuses on existing plans and future development. The program aims for ways to sustain existing water sources where the impacts of the drought have been very severe and to address the issues surrounding water demand management, such as ensuring nationwide water conservation campaigns[5].

In the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia in East Africa, the government launched several coordinated programs aimed at securing the water supply of drought-affected rural communities for basic usage. Water supply points have been established in different rural areas in the country using mobile sources to bring water to people. However, due to the severity of the drought, agriculture has been severely affected, leading the government to request emergency assistance from the international community for food and medical supplies[6].

In South Sudan, which is one of the youngest country in the world, internal challenges have been an obstacle to a coordinated response to the drought. Nevertheless, many non-governmental organizations are active in the country to assist the people in getting access to water.

3. Direct Drought Impacts on the Populace

Direct Drought Impacts on the Populace

Droughts are cyclical events around the world. The current drought has had a severe impact on water levels in dam reservoirs, causing some to run dry. The Hazelmere Dam in KwaZulu-Natal as at October 2015 was at 29% capacity—an all-time low—while the Kamuzu dams in Lilongwe, Malawi, were at less than 40% capacity in May 2016 at the peak of the drought (see Figure 3). The resulting low dam levels led to water restrictions being imposed on users across several countries in Southern Africa.

Additional impacts of the drought are death of livestock and poor crop yields due to poor or no rainfall making water unavailable for irrigation. Primarily attributed to El Niño*2, the drought has led to increased food prices and the United Nations estimates that 11 million children are at risk of starvation and inadequate water supplies in East and Southern Africa.

Areas in the Free State and North West provinces of South Africa that are known for corn farming are currently unable to grow enough corn due to the drought. In response, the government has declared about five provinces in the country to be disaster areas.

In Botswana, it was reported by the magazine African Business that the water level in the Okavango Delta was at its lowest in years at the peak of the drought. The Okavango Delta is the end point of rainwater that flows into the area each year from the highlands of the Republic of Angola. However, the scarce rainfall because of drought has made it practically impossible for houseboats and tour boats to navigate the waterways on tourist routes; it was only possible using makorro (dugout canoes).

The impact of the drought in South Africa has been most strongly felt in increased food prices. For example, the prices of meat and poultry, which are popular protein sources, are quite high, making it difficult for low-income households to purchase them. The government has resorted to importing food and poultry to augment local food production.

High-end homes located in suburban areas face local water restrictions that prohibit them from watering gardens and lawns and washing cars. These water restrictions are enforced simply by charging higher prices to users who exceed the allowed volume per day, and those who are found washing their car with clean tap water may face a stiffer penalty in some municipalities.

Countries such as Namibia, South Africa, and Botswana have experienced high cross-border migration due to the drought. Namibia has reported migration from Angola due to lack of rain in the Angolan border area, and Botswana has experienced an influx from Zimbabwe. South Africa has seen a huge influx from Zimbabwe, Malawi, Lesotho, Mozambique, and other neighboring countries because the drought has destabilized farming, which is the mainstay of economies in rural Africa.

In countries such as Angola, outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera have been reported since the onset of the drought. South Sudan, a young country with minimal basic infrastructure, has faced a huge challenge in water provision and has experienced an unprecedented level of cholera outbreaks due to unhygienic sources of drinking water. Local water suppliers have become desperate to supply water from any source because of the high demand for water despite the shrinking sources. As a result, the cost of selling water has increased due to the principles of supply and demand.

In Somalia and some parts of the Republic of Kenya, the cost of buying staple foods has increased while the cost of purchasing protein sources has dropped. Citizens in these parts are more concerned about just eating food rather than having a balanced diet in view of the crisis on the continent. Competition for arable land has also increased notably in West African countries such as the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the Republic of Cameroon, and the Republic of Niger, with seasonal fights reported between crop farmers and migrant pastoral grazers.

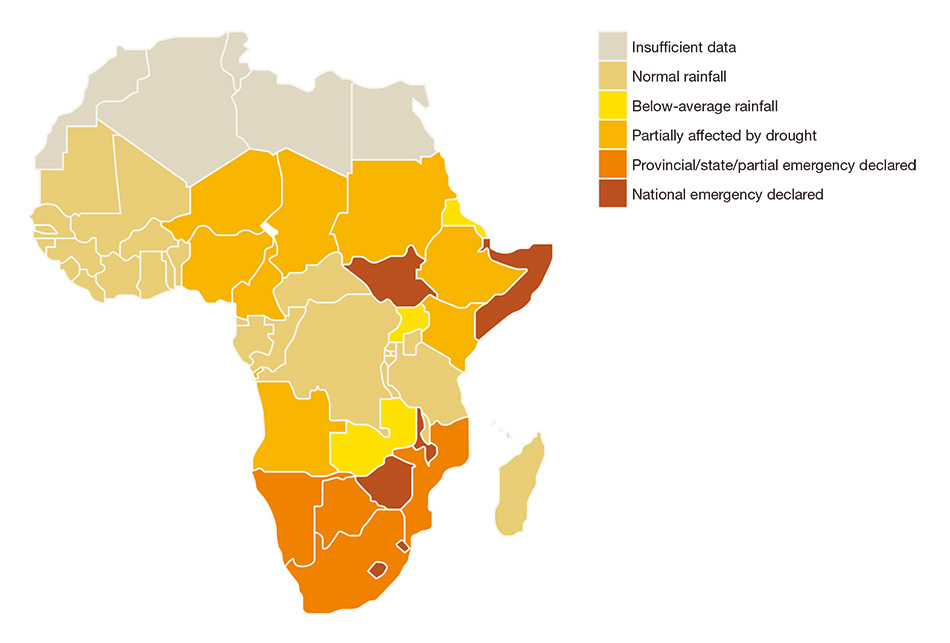

Figure 4 shows the situation of the drought in countries across Africa.

- *2

- El Niño is an extreme weather pattern comprising the warm part of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and disrupts the natural atmospheric circulation that brings rain to Africa. El Niño is often associated with high temperatures and heat waves.

Figure 4Map of Africa Showing the Situation of the Drought in Affected Countries

4. Water Policy and Security in Africa

Water Policy and Security in Africa Former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela said, “Access to water is a common goal. It is central in the social, economic and political affairs of the country, African continent and the world. It should be a lead sector of cooperation for world development.”

The future of water, agriculture, and energy has to be shaped in the present for future generations. Several African governments are drafting policies and master plans in order to guarantee water resources for the future. Countries such as South Africa, Namibia, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Lesotho are taking essential steps in this direction. Cross-border infrastructure developments are being considered. At the African Union, Agenda 2063 has been extensively discussed to ensure that services are delivered across all of Africa with ease of access for all its citizens.

Previous strategic discussions have included the United Nations Africa Water Vision for 2025, which addressed the equitable and sustainable utilization of water in Africa, socioeconomic development, and growth. The threats and challenges faced, as well as the current governance structures and systems for resolving the existing bottlenecks, were discussed. A practical approach to facilitate development of water infrastructure was suggested to ensure the provision of potable water to the whole continent.

With the aim of ensuring water security to sprawling urban populations, water security is being considered. These discussions are centered on finding alternative water sources that are not dependent on natural rainfall. Large- and small-scale seawater desalination is now a topic of discussion among decision makers and policy makers across all tiers of government in Africa. The mindset of the decision makers has shifted, and water security is now viewed as a pressing concern for the future. Discussions and talk alone are no longer enough, and there are calls for action and implementation across Africa.

In addition, reuse of treated wastewater was once considered taboo by many African citizens, but is openly discussed at conferences. There are discussions of reuse for industrial, agricultural, and domestic use. Movement in this direction offers a ray of hope to countries such as Namibia, where the City of Windhoek is acting as a pacesetter and providing an encouraging example by having successfully implemented reuse of treated wastewater for the past 40 years. An informative and educational approach is required for the spread of wastewater reuse. A look in this direction indicates there may be light at the end of the tunnel for Africa to reach its targeted growth and development goals.

5. Politics of the Drought and Water Provision

Politics of the Drought and Water Provision The involvement of different governments in finding solutions to the drought and water problems was highlighted during a visit to South Africa by the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi. One item on the agenda was how to assist South Africa in resolving its water challenges. Indian companies such as Ion Exchange (India) Ltd. signed partnership agreement with Stefanutti Stocks Holdings Limited to work together on water-related projects. The government of the Islamic Republic of Iran also signed bilateral agreements with the South African Government to jointly investigate the feasibility of seawater desalination in South Africa.

The drought has brought opportunities for various governments to work bilaterally on how to advance and secure water provision in their countries. In the quest to find solutions for the provision of water in Africa, the international relations and politics of water are moving forward. The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization of Japan recently signed a memorandum of understanding with the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality in South Africa in order to ensure that energy-saving and environmentally conscious desalination led by Hitachi, Ltd. is piloted in Durban in order to resolve the municipality’s water challenges.

6. Managing the Future: Financial and Technological Demands

Managing the Future: Financial and Technological Demands Companies such as Veolia Environnement S.A. are very active in the water sector in Africa, providing solutions for solving water and wastewater challenges. They provide competitive conventional and advanced water and wastewater technologies. A viable example is the Durban Water Recycling Project, a flagship public–private partnership (PPP) project for promoting water reuse. The agreement includes the major water users in eThekwini around the Bluff industrial area. The Veolia plant currently treats about 45 million liters per day (MLD) of domestic sewage effluent to graywater quality for reuse in the surrounding petrochemical refinery and paper and pulp mills. After about 20 years of operating the plant, the water purchase and water supply agreements are currently being renegotiated by the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality with old and new stakeholders interested in becoming part of the PPP arrangement.

A PPP program is in place to ensure the project becomes a reality. In light of the dire situation brought about by the drought, African governments are looking at new funding models for emerging water sources and the introduction of advance technology that can handle the required complexities and demands. One such example is the Port Nolloth Desalination Plant in South Africa, a small-scale plant that treats about 2.5 MLD, for which the government is providing about 80% of the funding and the successful implementing partner provides about 20% of the funding and executes a build-operate-transfer scheme. The implementing partner will operate the plant for three years and sell water to the municipality based on a water purchase agreement. In Port Elizabeth in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, a PPP for a 60-MLD desalination plant has been proposed by the government, which will guarantee the project. There is currently a strong drive by African governments interested in advanced water treatment processes to transfer the core responsibilities of funding, implementation, and operation to the private sector with an effective water purchase agreement. In view of these unfolding possibilities, it is important for international companies that have the capacity to provide solutions based on advanced technology, funding for mega projects, and execution to internally position themselves for such opportunities.

In conclusion, it is envisaged that as African countries strategically evolve in finding solutions for the essential service of water provision, bureaucratic red tape will be removed in order to accelerate development.

7.Increase in diseases

Increase in diseases Drought affects vital access to clean drinking water. This can lead to people drinking contaminated water, which brings about outbreaks of diseases like cholera and typhoid. These diseases can also spread in places with poor sanitation, another side-effect of having no clean water.

8.It can cause wildfires

It can cause wildfires Dry conditions can cause wildfires that burn remaining vegetation and endanger homes. Fires can also impact air quality and exacerbate chronic lung conditions.

Who is most affected by drought?

Droughts can occur all around the world. However, the effects of drought vary by region. What is considered a drought in the South Africa might not be considered a drought elsewhere.

Droughts bring the most risk to areas with high-pressure weather systems that are already prone to desertification. Developing countries are also more vulnerable to the socio-economic effects of drought due to a large percentage of their population being employed in the agriculture industry.

Over 36 million people have been impacted by the drought across Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia, which began in October 2020. Throughout these regions, insecurity, severe drought, and an exponential increase in food prices have brought millions to the brink of famine.

“Somalia is seeing the worst of the crisis, with over 200,000 already living in the most extremes of hunger, but the challenge is regional,” says Abukar Mohamud, IRC’s Deputy Director of Programs for Somalia. “Across East Africa, people are facing the worst drought in 40 years. By February 2023, up to 26 million people could experience extreme hunger if assistance isn’t drastically scaled up.

“People are not just dying due to a lack of food. Hunger means their weakened bodies cannot fight off diseases like diarrhoea, measles or malaria, so death rates are high. Children are particularly at risk and often die at double the rate of adults. And those who survive will face ill health for the rest of their lives. The 2011 famine saw over 250,000 people die of hunger – half of whom were children.”

Conclusion: What can be done to help the current drought in Africa?

East Africa is home to some of the IRC’s longest-running programs globally. Today, over 2,000 IRC staff in the region are scaling up our programmes to address the current drought and rising food insecurity, including expanding to new areas to meet severe needs.

This includes health programming, food and cash assistance, and providing clean water.

The IRC is calling for:

- A scale-up of funding – to immediately increase humanitarian resources to the affected regions.

- Unimpeded access – violence and insecurity continue to make it difficult for aid staff to operate in these areas. Humanitarian access is a right, not a privilege, under the Fourth Geneva Convention and related protocols.

- Coordination – for an effective response, both humanitarian and development actors must work jointly towards a common set of outcomes.

- Durable solutions – a long-term approach is essential to mitigating the lasting impacts of drought and famine, so that communities can reclaim their livelihoods and re-build resilience.

Sources: https://www.hitachi.com/rev/archive/2017/r2017_07/gir/index.html

: https://www.rescue.org/uk/article/what-drought-causes-impact-and-how-we-can-help

JOIN OUR TELEGRAM CHANNEL. CLICK HERE

Be the first to comment